Just a week into rehearsals, Atomic director Scott Miller commented that the musical was a bit of a departure from the type of bread-and-butter musicals New Line Theatre specialized in: the smart-ass, sassy, even absurdist comedy-dramas that are smart, but also often winking at the audience. Atomic is not that. It has moments of charm, humor, and even whimsy, but overall it's an earnest story, there's no irony in the performances. What's so weird about that? Well, because for years now, something as horrific as nuclear weapons and atomic warfare has been something of a joke, or sci-fi fantasy fodder.

Take one of the favorite cartoonists from my childhood, Gary Larson, creator of "The Far Side" comics. He had a fascination with them, for sure. Guys fishing spot mushroom clouds in the distance, and happily declare all fishing rules and regs null and void; a practical-joking physicist stands behind a colleague - who's assembling a nuclear weapon - ready to pop a bag and scare him; suburban housewives eyeball warheads in their neighbor's driveways like a new Chevy, and other fun stuff. This one is one of my favorites:

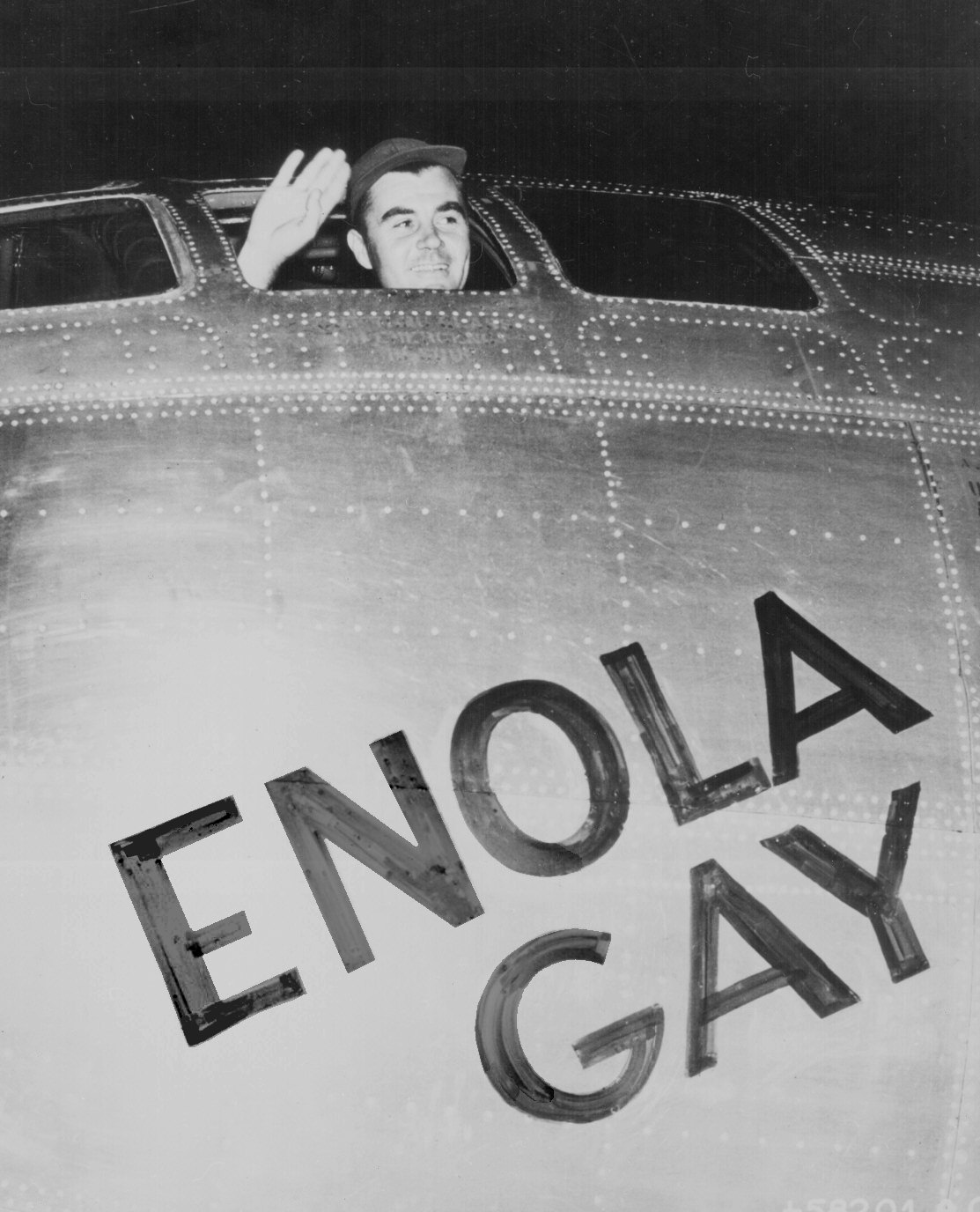

I had to ask my parents what the "trees with rings around them" were, and my dad's explanation was maybe my first exposure to nuclear weapons. For a kid growing up in the cold war era, "nukes" were of such a horrific, world-ending power, the only way we can wrap our minds around them is to joke. From the masterpiece Dr. Strangelove to the infamous scene of "nuking the fridge" in the latest installment of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, nuclear weapons are still scary, but like many scary things, we make light of them, we fetishize them, we write them in, all to gain a better understanding of what they mean and what we ourselves think of them.

| That's not how this works...that's not how any of this works! |

The challenge of Atomic is to set this aside for awhile. To compartmentalize the aforementioned comedy, as well as bits of horror-porn like the shocking scene from Terminator 2: Judgement Day where our heroine is blown to pieces by an atomic blast as she watches a bucolic scene of innocence (it's always a bucolic scene of innocence, isn't it?) on a playground, even the famously over-the-top political ad by the Lyndon B. Johnson 1964 presidential campaign:

Atomic takes place at a time when people were only first conceiving of what atomic warfare meant. Our main protagonist, Leo Szilard, over the course of the musical, is consistently trying to sound the alarm about the weapon's massive power and destructive capabilities. In his moving song, "the atom bomb is here," he correctly envisions what the bomb actually does and how it looks to its victims. It's a haunting moment. The writers here did most of the heavy lifting. For anyone exposed to pop culture in the past decades, it's a shocking and sobering trip back in time. Our challenge in this musical is to put the audience there and to have them feel the stakes these scientists and military officials must have felt, before the bomb became more of a sci-fi boogeyman and a metaphor for human folly. I'll still read "The Far Side" though, any day, but it's great to see an art form take such a straight-ahead treatment of this subject. I hope it gets audiences thinking and talking. After all, the atom bomb is still here.