|

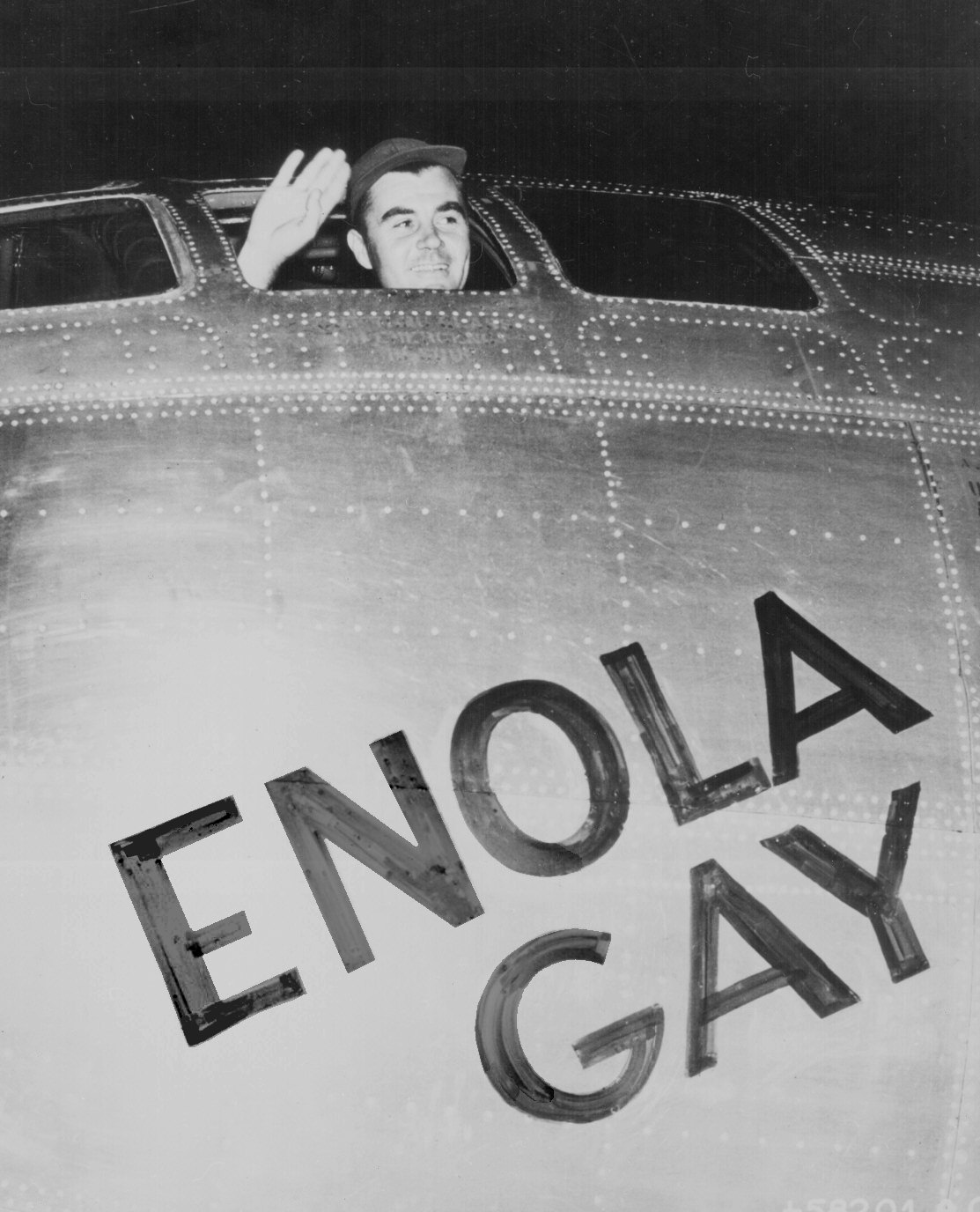

| Colonel Paul Tibbets Waves from his plane, the Enola Gay. |

In short? The original exhibit as planned, which was to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was scrapped and censored for a far more sanitized, even patriotic approach. The person who originally conceived the exhibit was Martin Harwit, a Cornell University professor, former serviceman and historian at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. What apparently made it controversial was that it attempted to capture not only the events that led up to the bombing, but also the real and lasting impact the bomb had on the people who were affected by it, including the scientists who created it, to the military team that dropped it, to the victims of it. It also questioned the common assumption that bombing the two cities in such a way saved lives instead of letting the war drag on. As news of the exhibit spread, Veterans' groups complained to the then largely conservative congress, and the Smithsonian was forced to bow to public pressure and remove some of the more "controversial" images, including photos of destruction and burned victims, etc. In addition, Harwit was forced to resign under the mounting pressure, almost in the same fashion Leo Szilard was pushed out of his own project. There was a lot at stake - a fight over what really happened, a fight over the moral high ground and certitude. We are still fighting this fight. You only need to check out the Amazon reviews of Harwit's account to see how divided we STILL are on this, and what exactly constitutes "revisionist history," a term that's been fought over a lot in recent years.

After 9/11, we saw this same type of fight to elbow out nuances and details - gray area - in the "war on terror." It became unpatriotic to even try to seek out why another cultural group - Muslim extremists - might want to kill Westerners, short of empty explanations that "they're evil" or "they hate our freedoms." It tends to have a chilling effect on discussion, even if it goes nowhere near unpatriotic sentiment. We're uncomfortable with gray areas. We don't like to see ourselves as culpable.

|

| The Genbaku Dome today is the site of a peace memorial. |

|

| The Hiroshima Genbaku Dome following the bombing. |

The 50th anniversary exhibit that never was - and what happened to it - has itself prompted a lot of writing and thinking about how we teach history, and how we remember it, and, as the hit musical Hamilton asks, "who lives, who dies, who tells your story?" The account in Judgment at the Smithsonian was probably a good meta-study for a student of history.

|

Throughout the musical, Szilard sees his research get away from him and become dangerous, almost like the chain reaction he helps discover. On the whole, Atomic is another way, another art form, to find and air out these moral questions once again. What it does well is that it makes the stakes once again feel high, even if the "language" of nuclear warfare, how we talk about it, and even the bomb itself - seem nowadays part of our everyday life...(to be continued).

No comments:

Post a Comment